Legend has it that in the midst of Plus500’s offices, close to Haifa’s balmy Mediterranean shores, there is a scale model of a casino, complete with a roulette wheel and blackjack table. Though the company’s employees probably wouldn’t like the comparison, the scale model, whether it exists or not, fits with Plus500’s origins.

Before it was launched in 2008, at least two of the six men that co-founded were involved in online gambling. Gal Haber and Alon Gonen, who would later put $400,000 of his own cash into starting Plus500, both worked together at InterLogic, a company that allowed people to play backgammon for money.

Prior to this, Haber worked as Chief Operating Officer for Casiopea Group – a company that appears to have run online casinos.

Though they are probably the most successful, Plus500 is not the only retail brokerage that has its roots in the gambling industry. AvaTrade, eToro, InterTrader and Markets.com are just some of the firms which have a connection to what is euphemistically called ‘online gaming.’

Gamification

Unsurprisingly, most people in the retail trading industry don’t like to draw attention to any connections they may have to the gambling world. Asked by Israeli outlet Globes in 2014 about the fact that many people have described Plus500 as a casino, Gonen said;

“I’m not sure that the people who think like that really understand what they’re talking about. It’s like saying that Bank Leumi is a casino, and I myself have an investment portfolio managed by Bank Leumi. It bothers me, but not too much.”

The origins of the gambling-trading crossover can be found in the early 2000s.

“In the industry we say that brokerages went through a process of ‘gamification,’” the former CEO of one major broker told Finance Magnates. “We saw a shift where companies started acting more like marketing machines than financial brokerages.”

That shift saw an explosion in the number of retail brokerages operating online. Though they were not the first of this ‘new breed’ of

David Ring, one of eToro’s Co-Founders, was a part of the founding team at 888.com – an online casino and poker site. Similarly, Negev Nosatzki had been a media buyer for Tradal, a company that performed marketing services for a number of major gambling sites, prior to launching AvaTrade.

The same year that those two firms were founded was also a significant period for the online gambling industry. It was in 2006, in an event now described as ‘Black Monday,’ that the US government effectively banned online gambling in America.

“The ban put a lot of people out of business,” said one industry insider. “Some of those people realised that, with online trading, they could use a lot of the same strategies to make money. That’s why a lot of firms established in the past 15 years had a very ‘game-y’ feel to them when they got started. Some of them didn’t even know that an a-book existed.”

Marketing and Technology

Ring and Nosatzki are emblematic of the two core skills that gambling workers brought to the trading industry; marketing and technology. The eToro Co-Founder was a software developer at 888.com and Nostazki was responsible for 40 percent of Tradal’s advertising budget.

“Online gaming people brought unique technological and marketing expertise to the trading industry,” said Tal Itzhak Ron, Chairman and CEO at legal firm Tal Ron, Drihem & Co., who works with both gaming firms and financial companies. “For gaming veterans, it was fairly easy to make the transition. Customer acquisition, for example, is similar in both industries.”

Conversely, with trading, there is supposed to be some logic to your decision making that can enable you to make money. The reason brokers provide so many analytical tools, for instance, is because they allegedly help you make better trading decisions.

But someone that approaches traders as if they were gamblers isn’t likely to make for a good broker. And, rightly or wrongly, the allegation that many brokers continue to treat clients like gamblers at a casino has continued to dog the industry.

Retail trading’s betting origins

Many of those allegations have come from within the industry itself. Back in 2013, for example, FXCM’s Brendan Callan appeared on CNBC and implied that many new entrants to the market, specifically those based in Cyprus, were bucket shops.

There is some level of irony to this sort of criticism because the retail trading industry’s roots lie in what is, even today, considered a form of gambling by the UK government – spread betting.

Just as the 2006 change in US legislation pushed many gambling workers to jump ship into trading, a British law, the 1960 Betting and Gaming Act, allowed spread betting companies to open shop.

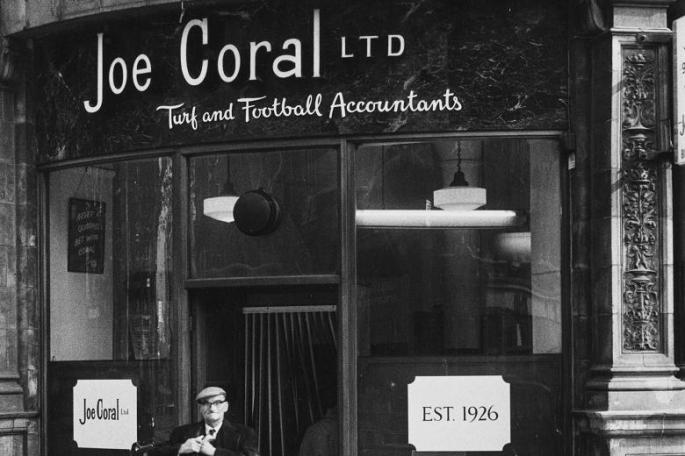

Amongst them were spread betting firms. The first to open, Coral Index, was founded by two stockbrokers, Arthur Levinson and Freddy Cheshire. Shortly after the Betting and Gaming Act was passed, the two business partners approached the owner of one the UK’s biggest bookmakers, Joe Coral, to start taking spread bets on financial markets.

Heading to the bookies

Coral, whose name hangs over betting shops throughout the UK even today, gave the pair his backing and in 1964 Coral Index started taking bets on the price of the FT30. Three years later, punters could also place bets on the price of the Dow Jones.

Significantly, the company was not registered as a financial services firm but as a bookmaker under the 1960 gambling legislation.

Though you wouldn’t know it today, in the past you could place spread bets with Wheeler’s firm on political outcomes and sports matches. In fact, a 1995 article published in Management Today indicates that 42 percent of the firm’s revenues in 1994 were from spread bets on football matches.

Similarly, in the early 1990s, City Index, another spread betting firm from the UK, was considering buying a casino in Las Vegas and Jonathan Sparke, one of the company’s Co-Founders, is also credited with creating sports spread betting.

All of this is not to say that brokers, old or new, are bad. It is simply to point out that moral criticism of the latter by the former should be taken with a grain of salt given the similar origins the two groups of firms share.

Since day one, the people running brokerages and spread betting firms have had a touch of the bookmaker to them. The question now is, with the introduction of the European Securities and Markets Authority’s (ESMA) product intervention measures, will that change?

Degamification

Everyone in the retail trading industry should be familiar with the European regulator’s newest rules. Introduced in , they restrict leverage and place marketing restrictions on brokers.

Advertising in particular was an area in which firms really let out the ‘gambling’ side of their operations. Sign up bonuses, massive leverage and competitions were all played up in exactly the same manner that betting websites and bookmakers advertise their services.

Technology helped with this. Brokers could reach huge numbers of people via online marketing efforts. At the same time, they could get clients to trade more than they ever had before.

ESMA’s rules negate any of the impact that those things had. Casino-style marketing is gone. Brokers may be able to reach large numbers of people but their ability to entice them to join their platforms has been depleted.

Similarly, the massive leverage that could be used to attract high-stakes traders is out of the window and, , it doesn’t seem like they’re upping their margins so that they can trade with the amount of money that was available to them previously.

In situations such as this, it’s convenient to draw an analogy between the past and the present. But in this instance there is no real comparison to be drawn, the retail trading industry hasn’t been in a situation like this before.

If the 2000s was the era of ‘gamification’ then perhaps the 2020s are going to be the years of ‘degamification.’ That will probably lead to better services for the average trader but, for those of us that like a flutter, it could be rather dull.

Be First to Comment